by Barry Peter Ould. When Grainger first visited Interlochen National Music Camp in 1930, he had already travelled far and wide from his native Australia, gathering folk tunes and concertizing in Britain as well as Europe and eventually in America where he and his mother, Rose arrived in September, 1914. Grainger’s first association at Interlochen was as guest conductor. By 1937 when he joined the faculty and began teaching there, he was attracted to the quiet, and to the idea of not travelling, and the salary he received was also appealing.

Grainger, with his wife Ella, lived in a cabin within earshot of the band shell. The days were long – private teaching from eight in the morning until 6:30 in the evening and evening rehearsals until ten o’clock. After this, Grainger would often practice until one or two in the morning. He was popular with the students, although the music he chose to teach was not. He remarked that he felt like “a lonely old crow on the bough.” He complained of being unable to find a talented student and was puzzled by the emphasis on developing piano technique – which came to him naturally. He told one student, “You can get more keyboard skill out of Bach’s 48 Preludes and Fugues than out of a boatload of studies by tone-deaf nit-wits like Czerny.”

Another student persisted in playing a piano passage faster than he was capable, explaining that he had heard Horowitz play it “like a blue streak in his recording.” Grainger dismissed the phenomenon by saying, “There likely wasn’t room on the recording at the right speed, so he had to hurry it up.”

Eventually the teaching and rehearsing got to be too strenuous, and Grainger became increasingly disillusioned with the staff and students at Interlochen. It was simply not the place for him. After his last summer there in 1944, he vowed, “I shall never teach again.” His wife echoed his sentiments by commenting, “It would have been so nice there if it wasn't for all those horrible children.”

The following list includes information on the concerts Grainger was involved in during his association with the Interlochen National Music Camp and I am indebted to their current archivist and librarian, Byron W. Hanson, for his work in compiling this information. I hope that this preliminary information will be of use to any future scholar who might be wish to undertake a more detailed study of Grainger’s time at the National Music Camp.

*The National High School Orchestra Camp was established in 1927 by music educator Joseph Edgar Maddy (1891-1966), and opened at Interlochen, Michigan in 1928. In a climate where school music provision was very limited, the camp was initially set up to provide opportunities for high school students to rehearse and perform together. By the 1930s, the Camp Orchestra was broadcasting for CBS and NBC radio, and in 1939 performed at the New York World’s Fair. One of the very few examples of Grainger on film is contained in the 1943 Interlochen publicity film, Youth Builds a Symphony, where Grainger is shown demonstrating the correct way to play Country Gardens to a throng of students as well as brief clips of him conducting, playing the Delius ‘Piano Concerto’, and running and leaping onto the podium to the shouts of “we want Grainger”.

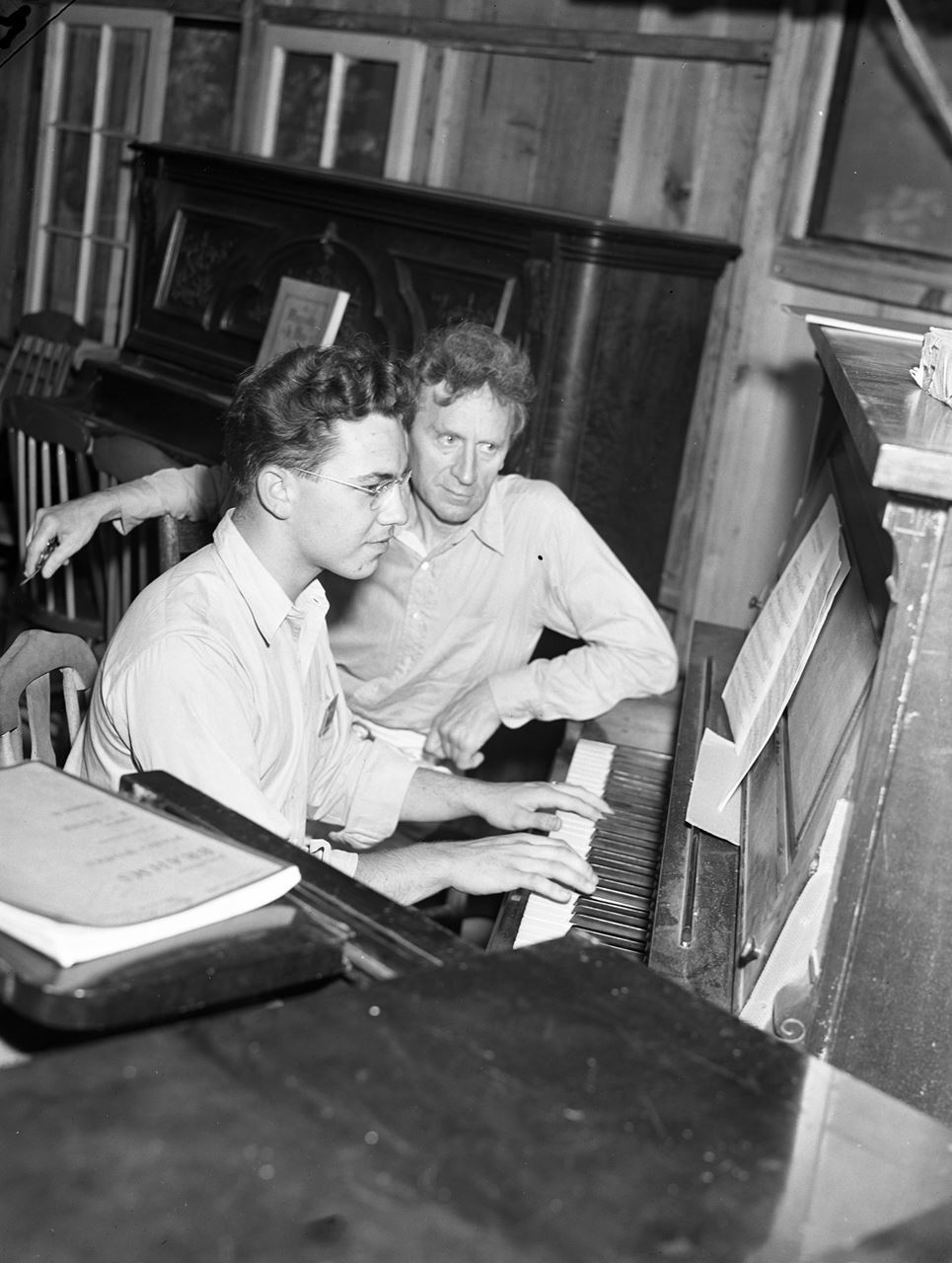

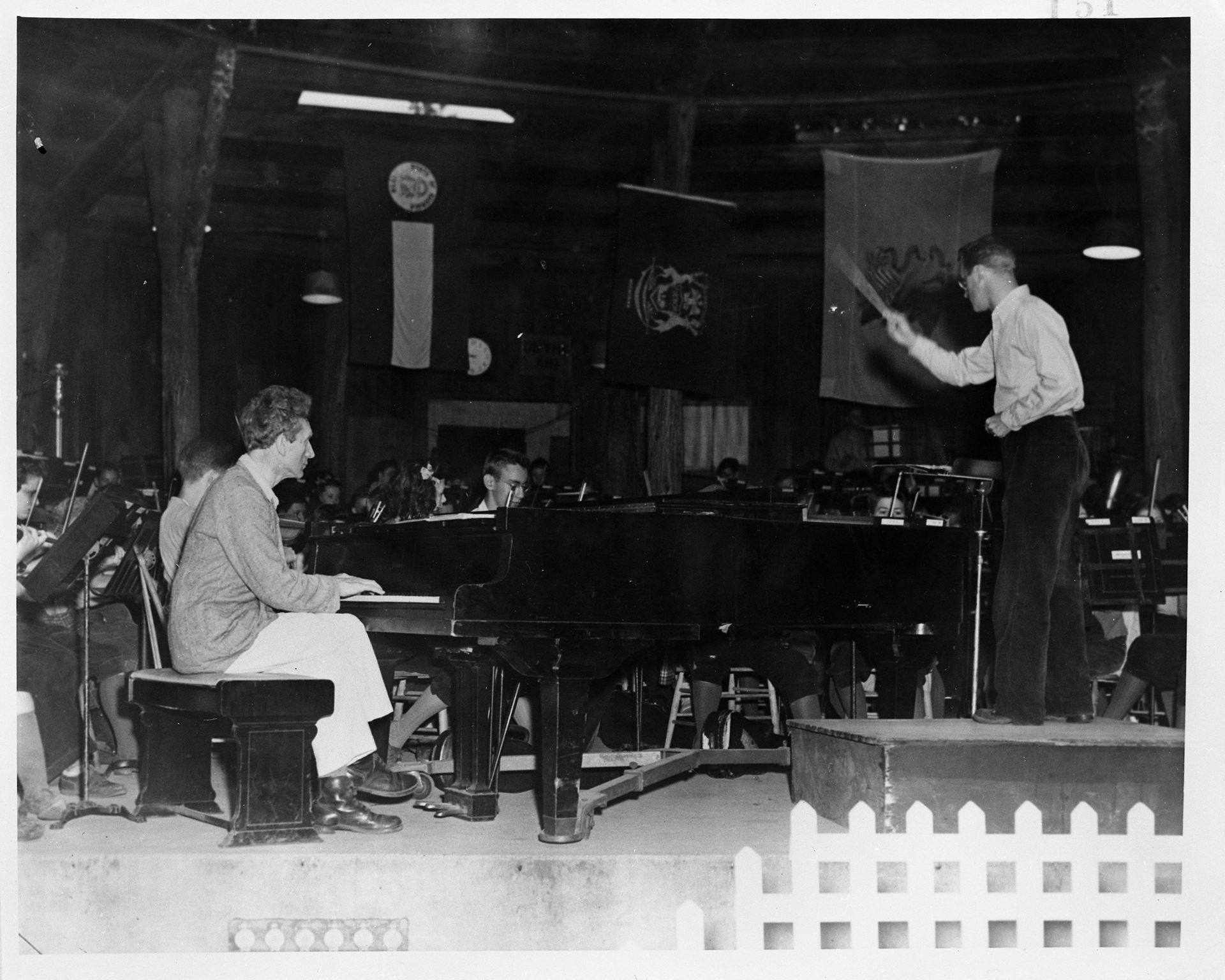

All photos taken between 1930 and 1944 at Interlochen National Music Camp.

1930

August 24 3:00pm PAG conducted a substantial concert featuring keyboard ensembles, band, orchestra, and choir. It began with his settings of Bach fugues in A minor (four pianists), C major (pianists and four harmonium players), and Purcell four-part fantasia No. 8 (pianos, harmoniums and string orchestra). The National High School Orchestra presented To a Nordic Princess and Spoon River. Next were five pieces for choir combined with various instruments: Australian Up-Country Song, Recessional (Kipling), The Hunter in His Career, Irish Tune, and Father and Daughter. Next came “Hillbillie’s Song”, a student work played by the orchestra conducted by the composer, Lee Briggs, then Marching Song of Democracy (choir and orchestra), and “Love Song” by Herman Sandby, played by a cello ensemble. The orchestra played Danish Folk Song Suite and the band closed with Children’s March and Shepherd’s Hey.

7:00pm The Camp’s third season closed with another substantial concert in two parts. The first part is indicated as being a broadcast, but considering that Les preludes and fifteen shorter works performed variously by band, orchestra, choir, a faculty cellist, and a tenor in a New York studio are listed, unless the broadcast extended beyond its customary hour it seems unlikely all were actually heard by the radio audience – unless severe cuts were taken. Part two indicates a somewhat shorter program, although part of the band’s portion is “a group of request numbers”. PAG is listed as conducting in part one only; the three works are Shepherd’s Hey (band), Irish Tune (choir), and Spoon River (orchestra).

1937

June 28 “Talk by Percy Grainger” followed 45’ orchestra sight reading.

July 1 Faculty concert – PAG played Cyril Scott’s arr. of Handel’s “Hornpipe from the Water Music and “Cherry Ripe”, followed by David Guion’s arrangement of “Turkey in the Straw”.

July 4 10:30am PAG gave talk at Interlochen Bowl Service: “The Characteristics of Spiritual Music”.

3pm National HS Band concert – PAG conducted a group of four early pieces “The Annunciation Carol”, Bach-Dolmetsch “March”, Bach Air from 3rd Suite, Fantasy (5-part) No. 1 (Jenkins), and later, “Irish Tune from County Derry”.

9pm NBC NHSO broadcast – JEM conducted “Spoon River” with PAG at the piano and John Hammond at the Hammond Organ. PAG repeated Annunciation Carol and the two Bach pieces from the afternoon concert, and conducted 1812 Overture and Irish Tune played by massed orchestra, band, and Hammond Organ [which had been but two years on the market]. PAG introduced the three early pieces on the air; Bill Kephart’s radio script printed in the following week’s booklet reveals that the Irish Tune preceded the 1812 overture, and both were played by the combined ensemble.

July 8 Faculty recital – played Brahms F minor clarinet sonata (Op.120/1) with Gustave Langenus.

July 11 3pm NHS Band concert – conducted Machaut “Ballad, No. 17”, Josquin “La Bernardina”, Gardiner “Shepherd Fennel’s Dance” and selection from Victor Herbert “Eileen”.

8pm NHSO concert – played 2nd and 3rd movements of Grieg concerto.

9pm broadcast – played 1st movement of Grieg, and repeated the Gardiner and Josquin pieces with NHS Band [Maddy conducted the concerto].

July 18 3pm NHS Band concert – PAG conducted Prelude in the Dorian Mode (Cabezón), Tuscan Serenade (Fauré), and O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sunde gross (Bach), and was at the piano for Children’s March, G. T. Overgard, conducting.

9pm repeat of Cabezón Prelude, and Children’s March.

July 21 7:30pm NMC Band – conducted Grieg “Norwegian Dance No. 1”, Irish Tune and Shepherd’s Hey, ”Funereal Chant” (Fauré) and Bach-Gounod “Ave Maria” with a cornet solo, then played piano in “Spoon River” with Overgard conducting. Bainum is credited for band arrangement of Spoon River.

July 29 Faculty concert – played piano (continuo) for 2nd Brandenburg Concerto, then duet with Skeat for C major fugue from WTC I/1 arr. for Hammond Organ and Bilhorn Folding Organ – no indication who played which. His piano ensemble class (4 pianos,16 hands) ended program with Fugue in E major (WTC II/90).

August 1 3:00pm NHSB concert – PAG conducted “A Children’s Overture” White), and his arrangement of “See What His Love Can Do” from Bach Cantata 85. [It may have been played in the afternoon and only trimmed from the evening broadcast due to time constraints. See comment below regarding broadcast radio script published in the following week’s program.]

8:00pm NHSO concert – played 2nd and 3rd movements of Tchaikovsky B-flat minor concerto.

9:00pm broadcast – played 1st movement of concerto (orchestra; Maddy) and conducted 1st performance of his arrangement of ”Fantasy and Air (Wm. Lawes). [The Lawes and the Bach cantata selection are both listed here and “1st performance” is noted for the Bach, but it is likely neither was played since they do not appear in the radio script published in the next week’s program.]

August 5 Faculty Concert – PAG played Brahms E-flat major clarinet sonata, Op. 120/2 with Burnet Tuthill.

August 8 3:00pm NSHB concert – conducted “Interlochen Camp Reel” (Cowell).

8:00pm NHSO – PAG and Clarke Kessler played mvts. 1 and 2 of Bach C major 2-piano concerto, Vladimir Bakaleinikoff, conducting.

9:00pm broadcast – they played the 3rd movement of Bach, and PAG conducted Cyril Scott’s “Festival Overture”. The Scott is not in the radio script published the following week, so likely was not broadcast.

August 12 Faculty concert – performed movements 3-4 of Beethoven violin/piano Sonata Opus 30/3 with Cecil Leeson, saxophonist/transcriber.

August 15 3:00pm NHSB concert – conducted Franck Chorale No. 1 (arr. Ralph Leopold) five Norwegian Folk melodies from Op. 66 (Grieg-Storm Bull), Josquin “Royal Fanfare”, and Fanfare to precede “La Peri” (Dukas).

8:00pm NHSO concert – “To a Nordic Princess” and Scott’s Festival Overture” were performed. PAG is listed only as conducting the Scott; Bakaleinikoff presumably led the Nordic Princess.

9:00pm broadcast – PAG conducted the NHSO in Le Carillon (Bizet), The Elf-hill (Herman Sandby), and “Molly on the Shore”. He is also listed as conducting the Franck Chorale and Storm Bull’s Grieg arrangements. [In the next week’s program, the radio script does not include the Franck and lists only 3 of the 5 Grieg movements.]

August 18 National Music Camp Band presented 8pm “Clinic Concert” at which a number of visiting band directors each conducted a selection announced only by number from a list of 24 pieces. Children’s March with PAG at the piano is No. 6 on the list. The printed comment saying only that “a program of nominal length will be chosen by the visiting band directors” offers no indication as to which of the listed pieces were played.

August 22 3pm NHSB concert—PAG conducted Two Pieces for “Tuneful Percussion” Instruments: Pagodas (Debussy-Grainger) and Eastern Intermezzo. Ella is listed among 16 performers; there is no indication of who plays what instrument(s).

8pm NHSO concert—PAG conducted Song of the High Hills (Delius).

1942 (little program information for this year – other performances likely)

August 16 High School Choir – “Australian Up-Country Song”, Henry Veld, conducting.

August 23 NHSO concert – “In a Nutshell Suite” PAG at the piano, probably Thor Johnson conducting. Final concert of summer.

1943

July 1 Conducted Irish Tune on WKAR broadcast (strings/horns).

July 6 Orchestra sight reading included Spoon River and Molly on the Shore. PAG played Grieg Concerto (unstated who conducted what).

July 14 Band sight reading included “Over the Hills and Far Away” (cond?).

July 17 7pm WKAR broadcast – PAG played Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue, Guy Fraser Harrison conducting.

8:30pm Faculty concert – PAG played Grieg G sonata with Stolarevsky. The Merry King was played by 12-piece wind ensemble – members unidentified.

July 18 Repeated Gershwin for evening concert.

July 20 Orch SR played Grieg Concerto, JEM cond. PAG cond. Molly (identical repertoire to 7/6: unusual: possibly an error, possibly a postponement.)

July 24 WKAR broadcast-conducted English Waltz, Harvest Hymn.

July 25 Repeated 7/24 selections for evening concert.

July 30 PAG (steel-string guitar) and Ella (gut-string guitar) did “Random Round”. Additional performers not identified.

July 31 7pm-Delius Concerto-3mvt version (TJ) for WKAR broadcast.

8:30-Solo recital

Star Spangled Banner

Fantasia and Fugue in g Bach/Liszt

The Carman’s Whistle Byrd

Handelian Rhapsody Cyril Scott

Etudes symphoniques, Op. 13 Schumann

Liebestraume #3 Liszt

Paraphrase on “Flower Waltz” Tchaikovsky-Grainger

August 1 NHSO concert – repeated Delius: 3 mvts listed, so original version.

August 13 7pm conducted band in Harkstow Grange [sic] and The Lost Lady Found from Lincolnshire Posey [sic].

8:30 conducted about 20 players in Pagodas, 1st of two pieces for tuneful percussion. Eastern Intermezzo was conducted by Thomas J. Glenecke.

August 14 Faculty concert – pianist in Quintet (from the Seventh Realm) by Fickensher.

August 15 Saxophone Quintet played the Four Note Pavane (Ferrubosco/Grainger) at morning service.

3:30pm PAG conducted band in all of Lincolnshire Posey [sic]. Considering that E. Rollin Silfies is listed as soprano saxophone soloist for Rufford Park Poachers, Grainger appears to have chosen the saxophone version. Composers Domenico Savino and Ferde Grofé also conducted their own works on this concert.

1944

July 6 Conducted The Four Note Pavan (strings) for WKAR broadcast.

July 14 Conducted “The Power of Rome and the Christian Heart” (band, string orchestra, organ and piano)WKAR broadcast “PREMIERE PERFORMANCE”.

July 15 NHSO broadcast (WKAR) – soloist for Morton Gould “American Concertette”, Homer LaGassey, conducting.

Faculty concert – Fauré Quartet No. 2, Op. 45 with Millard Taylor, Mihail Stolarevsky, and Allison McKown.

July 16 Afternoon – repeat performance of The Power of Rome…

Evening – repeat performance of “American Concertette”.

July 19 Band sight reading (LaGassey) – piano soloist for Children’s March.

July 29 Faculty concert – played “English Dance” for three pianists at two pianos with Marjorie MacKown and Guy Fraser Harrison.

July 30 High School Choir sang “Australian Up-Country Song”’ conductor probably Maynard Klein.

August 5 WKAR broadcast – played Gershwin “Concerto in F” with NHSO. Homer LaGassey likely conducted, as he is listed in next day’s concert program.

August 6 NHSO concert – “Concerto in F”.

August 12 NHSO broadcast WKAR – composer at piano for “Danish Folk Music Suite”. Also, Russell Howland’s “Sussex Psalm” was performed (“inspired by and dedicated to PAG and based on his harmonization of “A Sussex Christmas Carol”). Thor Johnson conducted entire program.

Faculty concert – PAG played “Lullaby from ‘Tribute to Foster’” and Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2.

August 13 NHSO concert – repeat of August 12 program. If the program is complete this would have been his last performance at Interlochen.

August 24 College Division Orchestra broadcast WKAR – student conductors led 16 pieces including “Spoon River”.