Etude Magazine and "The Jazz Problem"

In the 1920's, the editors of the music periodical Etude Magazine were scandalized by jazz. In their August, 1924 edition, whose cover is pictured here, the editors assembled a panel of thirteen musical experts, composers, conductors, and writers, each described as "distinguished," "well-known," "eminent," etc., to give their opinions on the merits (or lack thereof) of the musical craze sweeping America and Europe. The topic was continued in the following month, September, with another nine panelists. All were white men, with the exception of one woman, Amy Beach (identified as "Mrs. H.H.A. Beach, Renowned American Composer-Pianist").

In the 1920's, the editors of the music periodical Etude Magazine were scandalized by jazz. In their August, 1924 edition, whose cover is pictured here, the editors assembled a panel of thirteen musical experts, composers, conductors, and writers, each described as "distinguished," "well-known," "eminent," etc., to give their opinions on the merits (or lack thereof) of the musical craze sweeping America and Europe. The topic was continued in the following month, September, with another nine panelists. All were white men, with the exception of one woman, Amy Beach (identified as "Mrs. H.H.A. Beach, Renowned American Composer-Pianist").

The September, 1924 issue of Etude also contained an extended piece, based on an interview, by Percy Grainger (described as "Distinguished Pianist, Composer and Teacher"). Grainger had a long connection with Etude, as described in another blog, "Grainger's Contributions to The Etude Magazine 1915-1943" by Barry Ould.

The Etude editors made no secret of where they stood. In an opening editorial, "Where the Etude Stands on Jazz," they made it clear that they did "not endorse Jazz, merely by discussing it." They say that: "In its original form, it has no place in musical education and deserves none. It will have to be transmogrified many times before it can present its credentials for the Walhalla of music. . . In musical education Jazz has been an accursed annoyance to teachers for years. Possibly the teachers are, themselves, somewhat to blame for this. Young people demand interesting, inspiriting music. Many of the Jazz pieces they have played are infinitely more difficult to execute than the sober music their teachers have given them. If the teacher had recognized the wholesome appetite of youth for fun and had given interesting, sprightly music instead of preaching against the evils of Jazz, the nuisance might have been averted."

The editors go on, in a more benign spirit, to say that certain aspects of jazz, at least in its more domesticated versions, as composed by mostly white composers and played under mostly white conductors, were praiseworthy and could be tolerated: "... On the other hand, the melodic and rhythmic inventive skill of many of the composers of Jazz, such men as Berlin, Confrey, Gershwin and Cohan, is extraordinary. Passing through the skilled hands of such orchestral leaders of high-class Jazz orchestras conducted by Paul Whiteman, Isham Jones, Waring and others, the effects have been such that serious musicians as John Alden Carpenter, Percy Grainger and Leopold Stokowski, have predicted that Jazz will have an immense influence upon musical composition, not only of America, but also of the world."

A range of opinions on Jazz from "experts"

The actual opinions of the distinguished pundits varied a good deal, from scandalization to a view that jazz, at least in its Europeanized versions, was a harmless form of popular entertainment and even an important expression of the American spirit. Here is a selection:

George Ade ("American Humorist and Satirist")

Humorist George Ade said "The cruder form of "jazz," a collection of squeals and wails against a concealed back-structure of melody, became unbearable to me soon after I began to hear it." But he concedes, saying "It can be a dreadful disturbance to the atmosphere when perpetrated by a cluster of small-town blacksmiths and sheet metal workers but it becomes inspiriting and almost uplifting under the magical treatment of Paul Whiteman and some of his confreres."

Mrs. H.H.A.(Amy)Beach ("Renowned American Composer Pianist")

Composer Amy Beach's objections were less to the music itself than to the dances that went with it: "If it is merely a question of interesting new rhythms, accompanied by weird harmonics and suggested by lilting melodies, no one could appreciate the charm of such combinations more fully than I, provided that the work is good throughout. Taken, however, in association with some of the modern dancing and the sentiment of the verses on which many of the 'jazz' songs are founded, it would be difficult to find a combination more vulgar or debasing."

John Alden Carpenter ("Distinguished American Composer")

Composer John Alden Carpenter was more accepting, "deprecating the tendency to drag social problems into a discussion of contemporary American music." In his opinion, "I am convinced that our contemporary popular music (please note that I avoid labeling it 'jazz') is by far the most spontaneous, the most personal, the most characteristic, and, by virtue of these qualities, the most important musical expression that America has achieved. I am strongly inclined to believe that the musical historian of the year two thousand will find the birthday of American music and that of Irving Berlin to have been the same."

John Philip Sousa ("Famous Composer-Conductor")

John Philip Sousa was one of the most benign. He begins with a quip: I heard a gentleman remark, "Jazz is an excellent tonic but a poor dominant." He blames poor performances for the lack of acceptance of jazz, concluding, "There is no reason, with its exhilarating rhythm, its melodic ingenuities, why it should not become one of the accepted forms of composition. It lends itself to as many melodic changes as any other musical form. Forms go by cycles. There was a time when the saraband and the minuet occupied the center of the stage, and to-day the fox trot, alias jazz, does, and like the little maiden:—

"When she was good, she was very, very good

And when she was bad she was horrid."

Leopold Stokowski ("Distinguished Orchestral Conductor")

The September, 1924 issue of Etude continued with more critiques. Leopold Stokowski (quoted from "an address before the Forum in Philadelphia") also offered complimentary remarks:

"'Jazz' has come to stay. It is an expression of the times, the breathless, energetic, super-active times in which we are living, and it is useless to fight against it. Already its vigor, its new vitality, is beginning to manifest itself. The Negro musicians of America are playing a great part in this change. They have an open mind, and unbiased outlook. They are not hampered by traditions or conventions."

The last remark is of course not true. Stokowski ignores the rich traditions that lay behind the origins of jazz

Clay Smith ("Well-Known Chautauqua Performer and Composer of Many Successful Songs")

Musician Clay Smith, speaking of the supposed scandalous origins of the word "jazz," brought to the discussion a different perspective, emphasizing the role played by the playing of jazz in the dance halls and honky-tonks of western mining towns, where the writer had played trombone as a youth. In fact, he considered these the true birthplace of jazz (together with its "vulgarity"): "The primitive music that went with the 'Jazz' of those mining-town dance halls is unquestionably the lineal ancestry of much of the Jazz music of today. The highly vulgar dances that accompany some of the modern Jazz are sometimes far too suggestive of the ugly origins of the word."

Smith ends by grudgingly approving some of the more "cosmopolitan" forms of popular jazz, and concludes, with a nod to Stravinsky and Grainger: "But, even the best of this entertaining and popular music has no place with the great classics or even with fine concert numbers, except perhaps in a few cases where musicians of the highest standing, such as Stravinsky, Carpenter, Cadman, Guion, Grainger, Huerter and others with real musical training, have playfully taken 'Jazz' idioms and made them into modernistic pieces of the super-jazz type."

Grainger's answer to the critics

Percy Grainger's rebuttal to the critics appeared in the same September, 1924 issue of Etude. The article was the result of an exclusive interview "secured expressly for The Etude." Grainger was enthusiastic about jazz as a new form of popular music. He is frank about the fact that he is speaking of the highly modernized form of jazz that was currently being played. As would be expected of Grainger being Grainger, he saw jazz in the light of his own obsessions, especially his infatuation with all that he saw or imagined as "Nordic." He saw no reason to get upset over jazz. "What is this bug-a-boo about Jazz" he says. "Jazz differs not essentially or sociologically from the dance music all over the world, at all periods, in that its office is to provide excitement, relaxation and sentimental appeal. In this respect it differs not from the Chinese or native American Indian music or from the Halling of Norway, the Tarantella of Italy, Viennese Waltzes, Spanish Dances or the Hungarian Czardas. The trouble is that too much fuss is made about Jazz. Much of it is splendid music. Its melodic characteristics are chiefly Anglo-Saxon—closely akin to British and American (white) folk-music."

Jazz as "Nordic" music

He renders the opinion of jazz that "Its excellence rests on its combination of Nordic melodiousness with Negro tribal, rhythmic polyphony plus the great musical refinement and sophistication that has come through the vast army of highly trained cosmopolitan musicians who ply in Jazz. There never was popular music so classical." He enlarges on the theme of Nordic heritage, which he saw as related to living in large, open spaces: "The music of all free peoples has a wide melodic sweep. By free I mean those people with strong pioneer elements--people who live alone in isolated situations. This accounts for the great melodic fecundity of the Nordic race. folk who live in congested districts cannot be expected to write melodies with wide melodic range..."On the other hand, the Scandinavian, the Englishman, the Scotchman, the Irishman, whether he be in his native land, an American cowboy or an Australian boundary rider, is often solitary in his music-making; and his melodies have, therefore, wider range of melodic line, as in such a tune as Sally in Our Alley or the Norwegian Varmlandsvisa."

He goes on: "This strong Anglo-Saxon element preserved in America was musically mixed with the equally virile rhythmic tendencies of the Negro. The Negro is not natively melodic, in the bigger sense. His melodies are largely the evolution of tunes he as absorbed from his white surroundings. His musical instinct is rhythmic first of all. (Note the Negro folksongs collected in Africa by Natalie Curtis.) [Not quite so: Curtis' African folksongs, while authentic, were collected from Africans actually living in America, at the Hampton School in Virginia.] Grainger recognized some non-"Nordic" influences: "To this came, doubtless, via San Francisco, about ten years ago, some Asiatic influences which in turn were to make some of the other elements of Jazz." He mentions the use of notes that are sometimes a quarter-tone or so "off key," apparently in reference to the "blue notes" common in jazz.

Grainger was enthusiastic about the introduction of new instruments in jazz, especially in percussion, including the xylophone and bells, and about the use of the saxophone. Grainger himself played the saxophone, and wrote many pieces for band, featuring every type of saxophone.

Relationship of jazz to classical music

Grainger was less sanguine in this article about the long-term prospects of an influence of jazz on classical music. "Apart from its influence upon orchestration, Jazz will not form any basis for classical music of the future, to my mind. . . On the other hand, it has borrowed (or shall we say 'purloined'?) liberally from the classical. The public likes Jazz because of the shortness of its forms and its slender mental demands upon the listener. . . On the other hand, length and the ability to handle complicated music are invariable characteristics of really great genius. We realize this if we compare the music of Bach, Beethoven, Wagner, Delius and Tchaikovsky with the music of such fine but smaller musical talents as Scarlatti, Jensen, Roger Quilter, Reynaldo Hahn and others."

In education, Grainger advocated relieving the student's musical diet with classical training: "In the education of the child, Jazz ought to prove an excellent ingredient. But he also needs to drink the pure water of the classical and romantic springs." However, Grainger's views on the relationship between Delius and at least some kinds of jazz would change in a few years, especially after reading an article on Duke Ellington and Delius by R.D.Darrell.

R.D. Darrell's comparison of Ellington to Delius, and its effect on Grainger

In the periodical Disques for June, 1932, the critic R.D. Darrell wrote a critical appreciation of the music of Duke Elllington called "Black Beauty," after one of Ellington's compositions. It was the first in-depth study of Ellington's music. Darrell saw a similarity between Ellington and Delius, whom he also praises lavishly: "The Teutonically romantic-minded find an experience in Bruckner and Mahler that is shoddy and over-blown to those who find their rarest musical revelation in the pure serenity and under-statement of Delius." He saw in Ellington's music a similar "fluidity and rhapsodic freedom." He also saw a unity of composition that, in his view, could not be created by improvisations by a group of musicians, saying "And where the music of his race has heretofore been a communal, anonymous creation, he breaks the way to the individuals who are coming to sum it up in one voice, creating personally and consciously out of the measureless store of racial urge for expression." Darrell proceeds to quote another critic who says of Ellington's music "So homogeneous he is that it is sometimes hard to tell where folk song ends and Delius begins."

In the periodical Disques for June, 1932, the critic R.D. Darrell wrote a critical appreciation of the music of Duke Elllington called "Black Beauty," after one of Ellington's compositions. It was the first in-depth study of Ellington's music. Darrell saw a similarity between Ellington and Delius, whom he also praises lavishly: "The Teutonically romantic-minded find an experience in Bruckner and Mahler that is shoddy and over-blown to those who find their rarest musical revelation in the pure serenity and under-statement of Delius." He saw in Ellington's music a similar "fluidity and rhapsodic freedom." He also saw a unity of composition that, in his view, could not be created by improvisations by a group of musicians, saying "And where the music of his race has heretofore been a communal, anonymous creation, he breaks the way to the individuals who are coming to sum it up in one voice, creating personally and consciously out of the measureless store of racial urge for expression." Darrell proceeds to quote another critic who says of Ellington's music "So homogeneous he is that it is sometimes hard to tell where folk song ends and Delius begins."

As we see below, there was actually a good deal of collaboration and improvisation in the works of Ellington, but it was behind the scenes, codified by the time the public heard them. Darrell's piece was to have a great influence on Grainger's views, connecting Ellington to Delius, which would lead to Ellington being invited by Grainger to New York University.

Delius in Florida

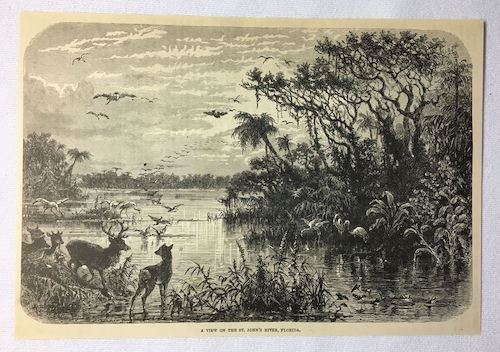

The reference to Delius was not far-fetched. Frederick Delius was the son of a prosperous British wool merchant of German origin, and was expected to follow in his father's business. In 1884-1885 he escaped this life by having his father send him to Florida to run an orange plantation on the St. John's River (pictured in an 1886 engraving). There he heard the songs of the Black laborers, as well as the songs of crew members on passing ships. In 1886, his father relented, and allowed him to go to study music in Leipzig. But he never forgot the influence of songs he heard in Florida. His Florida Suite alternates between dreamy, impressionistic movements evoking the Florida landscape from dawn to sunset and sprightly dances. The first movement, "Daybreak," ends with a version of the dance "La Calinda."

Delius was a friend of Percy Grainger, and he once proposed, as reported in John Bird's biography of Grainger, that they work together on a collection of "negro folk-songs" in America.

Percy Grainger at New York University - a short-lived career

In 1932-33 Percy Grainger was appointed Associate Professor of Music at New York University. There, he gave a lecture series called "A General Study of the Manifold Nature of Music." It was to be a short-lived career. Grainger and the formal academic life were not a good fit. His lectures were not well-attended. However, the session at which Ellington and his orchestra performed was packed to overflowing. He prepared his students by leading a discussion of Darrell's article in Disques. Ellington's participation was probably arranged by Ellington's manager Irving Mills, who wanted to establish Ellington's reputation as a "legitimate" composer, respected by classical musicians.

Grainger's lecture notes for the the class survive at the Grainger Museum in Melbourne. Some of them are reproduced in Laura Rexroth, "Duke Ellington and Percy Grainger: Black, Brown, and 'Blue-Eyed English'" in Frank J. Cipolla and Donald Hunsberger (eds.) The Wind Band in and Around New York ca. 1830-1950 (publ. 2005). A photo of Mills, Grainger and Ellington, who is playing the piano, (also reprinted in the article) is at the Museum in Melbourne.

Grainger is said to have opened the class by announcing, "The three greatest composers who ever lived are Bach, Delius and Duke Ellington. Unfortunately Bach is dead, Delius is very ill but we are happy to have with us today The Duke."

After the lecture and discussion, the Ellington Band played several selections, including Creole Love Call, Creole Rhapsody, and Tiger Rag. Grainger had the band improvise upon some tunes, whose identity is not preserved, then he himself sat down at the harmonium and piano and played selections by Ole Bull and Grieg. It is not known whether Ellington stayed around for this part of the class.

Nordic strains and Free Music machines

Grainger by now had added another element to his identification of jazz with "Nordic" music. By now he was developing his ideas of "Free Music," music unconstrained by pitch or tempo, like the sounds of nature in the waves and wind. This interest would culminate in his Free Music Machines, proto-synthesizers that he would develop with science teacher Burnett Cross. In the gliding glissandos and "blue notes" of jazz, Grainger saw a precursor of Free Music. In his class notes we find the note "The gliding and off-pitch sounds in jazz considered an important step to the free music of the future." (A discussion of Grainger's Free Music Experiments by Paul Jackson and Susan Colson is available on YouTube.)

Ellington's Creole Love Call and his artistic borrowings

Creole Love Call (with its name evoking the then popular Indian Love Call of Rudolf Friml), was an interesting choice. First performed at the Cotton Club in Harlem, a nightclub where black entertainers (the women were always light-skinned) performed for white audiences, it was the piece that first made the reputations of Ellington and vocalist Adelaide Hall. They recorded this hit in 1927. (You can hear Adelaide Hall's performance on YouTube.) Hall sings in wordless song, in imitation of the instruments, reversing the usual practice of jazz, where instruments echo the human voice.

Although Grainger and other critics saw Ellington's music as representing the inventiveness of a single genius, his pieces were always collaborative. During rehearsals, individual members of the group improvised, and variations that Ellington liked were incorporated by Ellington into a final, unified composition. One of the most important members of his group was pianist and lyricist Billy Strayhorn, who was the actual composer of one of Ellington's most famous songs, "Take the A Train." In the case of Creole Love Call, the melody actually originated with New Orleans jazz great "King" Oliver, who recorded it in 1923 as "Camp Meeting Blues" with his Creole Jazz Band. The melody was brought to Ellington by reedman Rudy Jackson, who claimed it as his own composition. Oliver sued Ellington, but Oliver, a better musician than he was a businessman, had never properly copyrighted the song, and Ellington, even after he learned his error (and fired Rudy Jackson) had no qualms about copywriting the composition as his own. Adelaide Hall, too, played a part in the creation of Creole Love Call. She told how she came to sing the vocal version with Ellington:

Adelaide Hall, too, played a part in the creation of Creole Love Call. She told how she came to sing the vocal version with Ellington:

"I was standing in the wings behind the piano when Duke first played it. I started humming along with the band. Afterwards he came over to me and said, 'That's just what I was looking for. Can you do it again?' I said, 'I can't, because I don't know what I was doing.' He begged me to try. Anyway I did, and sang this counter melody, and he was delighted and said 'Addie, you're going to record this with the band.' A couple of days later I did."

Creole Love Call made Ellington and Hall a big hit at the Cotton Club and eventually worldwide. The picture at right shows Adelaide Hall in Blackbirds of 1928.

Ellington on Delius and on Porgy and Bess

Ellington did not really see any resemblance between his music and Delius', but the experience at NYU led him to find out more about Delius. He liked the music, and his favorite work by that composer was In a Summer Garden. He listed his other favorite classical pieces as Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe, Debussy's La Mer and Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, and Holst's The Planets.

Ellington had a similar appreciative but critical attitude toward the supposed "Negro" melodies of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess. In an interview quoted in The Duke Ellington Reader (ed. Mark Tucker), he gave his opinion: "Grand music and a swell play, I guess, but the two don't go together. . . The first thing that gives it away is that it does not use the Negro musical idiom. . . It was not the music of Catfish Row or any other kind of Negroes."

Ellington always saw his music as solidly within the African-American tradition. It was not Nordic or European or anything else. He did not like to call his music "jazz," but in Rhythm, March, 1931 (quoted in Darrell, "Black Beauty") he said: "The music of my race is something more than the 'American idiom.' It is the result of our transplantation to American soil, and was our reaction in the plantation days to the tyranny we endured. What we could not say openly we expressed in music, and what we know as 'Jazz' is something more than just dance music . . . There is no necessity to apologize for attributing aims other than terpsichorean to our music, and for showing how the characteristic, melancholy music of my race has been forged from the very white heat of our sorrows, and from our gropings after something tangible in the primitiveness of our lives in the early days of our American occupation. . . I think that the music of my race is something which is going to live, something which posterity will honor in a higher sense than merely that of the music of the ball-room of today."

Ellington and Grainger: Two worlds touching but not quite communicating

Ellington and Grainger seem never to have met again, but both men, we hope, got something from the encounter. Ellington got the respect he needed for his career from the musical establishment, and perhaps an opportunity to increase his pleasure in classical music. Grainger could point to additional "proof" of his musical theories.