By Cora Angier Sowa. What is that strange object?

What is that strange object in storage on the top floor of the Grainger House at 7 Cromwell? (We hope to raise funds to conserve and put it on display.) It looks like a demented beach chair, half folded up. It is, in fact, a small model of Percy Grainger's biggest idea, the Free Music Machine, a device to produce music that was like the sounds of the real world, unconstrained by conventional pitch and rhythm. Designed in the last years of his life, he felt that it was his "only important contribution to music."

What is that strange object in storage on the top floor of the Grainger House at 7 Cromwell? (We hope to raise funds to conserve and put it on display.) It looks like a demented beach chair, half folded up. It is, in fact, a small model of Percy Grainger's biggest idea, the Free Music Machine, a device to produce music that was like the sounds of the real world, unconstrained by conventional pitch and rhythm. Designed in the last years of his life, he felt that it was his "only important contribution to music."

His fascination with the sounds around him

From the time he was a child, Percy Grainger was obsessed with sounds. In Melbourne, Australia, where he grew up, his mother would take him boating on the lake in Albert Park, where he was fascinated by the sound of the waves lapping against the boat, as well as by their visually smooth shapes. He spent hours listening to the eerie sounds of the wind as it blew down chimneys or through the telegraph wires. These experiences led Grainger to want to create music that was continuous, like the real, continuously fluctuating world.

The sounds of the railroad train provided another source of pleasure. On a trip through Europe as an adult with his mother, as described by John Bird in his biography of Grainger, "It was whilst travelling by train in southern France and Italy that Percy was suddenly struck by the rhythmical complexities of the sounds penetrating the railway carriage as it rattled over point systems. For Percy this single experience touched off a desire to make radical experiments with irregular rhythms in music."

A squeaky door

Daniel N. Leeson, U.S. Army computer specialist and clarinettist, was assigned to an IBM office next door to Grainger and they became acquainted. He tells the following story, quoted in Portrait of Percy Grainger by Malcolm Gillies and David Pear: "I once saw him open and close a closet door in his house 15 or 20 times because a new and different kind of squeak had developed in the hinge and he found the sound interesting." Leeson also tells how Grainger turned down eating in a fancy restaurant in favor of his favorite donut shop, where there was a jukebox. He was particularly fascinated by new records by Elvis Presley because of his sound: "Listen to that sound! It's really wonderful!!"

Making the piano resonate like an orchestra

Many know Grainger only as a collector, arranger, and adapter of folk tunes, in such simple forms as "Country Gardens" or in reimagined works like "Lincolnshire Posy." Band musicians are eternally grateful to him for his prodigious output of band music. In his own day, he was known as a virtuoso pianist, interpreter of Grieg, Tchaikovsky, and Bach. But even here, he was fascinated by producing sounds that only he could hear in his head. In a masterful lecture and demonstration at the Percy Grainger Piano Mini-Festival in White Plains in May, 2018, composer and International Percy Grainger Society Vice President Mark Grant demonstrated some of the tricks used by Grainger to produce the sound he wanted, in particular using the resources of the piano to sound like an orchestra. These included playing arpeggiated chords ("harping sounds," he called them), and raising or lowering the center (or "sostenuto") pedal of the piano to make selected chords continue, then fade away. (To listen to Mark's entire presentation, click here.)

Free music finally created

But the desire to create the continuous sounds he could hear in his head never left Grainger. In 1938, he said,

"...Out in nature we hear all kinds of lovely and touching 'free' (non-harmonic) combinations of tones, yet we are unable to take up these beauties and expressiveness into the art of music because of our archaic notions of harmony.

"Personally I have heard free music in my head since I was a boy of eleven or twelve in Auburn, Melbourne. It is my only important contribution to music ... Yet the matter of Free Music is hardly a personal one. If I do not write it someone else certainly will, for it is the goal that all music is clearly heading for now and has been heading for through the centuries. It seems to me the only music logically suitable to a scientific age." (Grainger's Statement on Free Music, 6 December 1938, Grainger Museum, University of Melbourne, Australia, quoted in Penelope Thwaites, The New Percy Grainger Companion.)

Grainger first tried using available instruments, such as the theremin (invented by Léon Theremin), played by waving the hands between two antennas attached to oscillators, one antenna controlling the frequency, the other the volume. He modified a piano to play microtones (the "Butterfly Piano"), but this was not satisfactory, as the tones still moved in stepwise progression, not with the gliding movement he desired.

The Reed-Box-Tone-Tool, the Kangaroo Pouch and the electronic Free Music Machine

In 1945 he met Burnett Cross, a high school science teacher who also had a background in music. In a collaboration that lasted for the rest of Grainger's life, the two developed increasingly sophisticated machines (which were also of increasing size, eventually filling most of an entire room). On early versions, they experimented with hitching together arrays of Solovoxes, electronic instruments manufactured by the Hammond Corporation. A version called the Reed-Box Tone-Tool used harmonium reeds, played by punched paper tape like that used to control player pianos, with suction from a vacuum cleaner applied to its back. As they tinkered, they built contraptions out of all kinds of "found" materials. John Bird describes the process in his biography of Grainger:

In 1945 he met Burnett Cross, a high school science teacher who also had a background in music. In a collaboration that lasted for the rest of Grainger's life, the two developed increasingly sophisticated machines (which were also of increasing size, eventually filling most of an entire room). On early versions, they experimented with hitching together arrays of Solovoxes, electronic instruments manufactured by the Hammond Corporation. A version called the Reed-Box Tone-Tool used harmonium reeds, played by punched paper tape like that used to control player pianos, with suction from a vacuum cleaner applied to its back. As they tinkered, they built contraptions out of all kinds of "found" materials. John Bird describes the process in his biography of Grainger:

"All kinds of junk were utilized as well as the more common items which were bought at local hobby and hardware stores. At times Ella and Percy would don their finest clothes to avoid police suspicion and spend part of an evening rummaging amongst the piles of rubbish by the back doors of department and furniture stores. Eventually the machines employed such improbable articles as pencil sharpeners, milk bottles, bamboo, roller-skate wheels, the bowels of a harmonium, linoleum, ping-pong balls, children's toy records, egg whisks, cotton reels, bits of sewing machines, carpet rolls, a vacuum cleaner, a hair dryer, and, of course, miles of strong brown paper and string."

For Grainger, invention came easily. One of his inventions was a roller for holding the pages of a musical score in one long roll instead of separate pages that had to be turned. Penelope Thwaites sums up Grainger's inventiveness as "a kind of outback ingenuity common to the older traditions of Australia and the U.S. ... a resourceful use of available materials summed up in story and song in the phrase 'stringybark and greenhide'..."

(In the interests of full disclosure: As a child I myself invented a "rubber band guitar," consisting of a cigar box with rubber bands wound around it, tuned by stretching the bands to make different notes — Note: I later became a harpist! I also made a "milk can marimba" out of small condensed milk cans, played with a stick. There's nothing like inventing your own instrument to stimulate the mind.)

Perhaps the most famous of Grainger and Cross' machines was the "Hills and Dale" or "Kangaroo Pouch," which had rolls of paper with the edges cut in a wavy pattern, made to turn on a roller. As the roll revolved, mechanical followers rode the outline cut into the side of the paper, controlling the pitch of a set of oscillators and the volume of the amplifiers. In the beginning, Grainger wanted nothing to do with the electronic synthesizers that were being invented by others. He felt that their inventors approached the problem wrong end to, inventing a device, then searching for something to do with it, whereas he started with the music, then searched for a means of realizing it. The final version of the Free Music Machine was, however, purely electronic. In the last version, the cut paper outlines were replaced by patterns painted on rolls of clear plastic. A row of spotlights shining through the plastic projected light beams onto an array of photocells, which in turn controlled the oscillators. The inventors were working on this device at the time of Grainger's death. A full description of all permutations of Grainger and Cross' radical inventions, with illustrations, appears in Rainer Linz, "The Free Music Machines of Percy Grainger," first published in Experimental Music Instruments, Vol. 12, No.4, 1997.

Perhaps the most famous of Grainger and Cross' machines was the "Hills and Dale" or "Kangaroo Pouch," which had rolls of paper with the edges cut in a wavy pattern, made to turn on a roller. As the roll revolved, mechanical followers rode the outline cut into the side of the paper, controlling the pitch of a set of oscillators and the volume of the amplifiers. In the beginning, Grainger wanted nothing to do with the electronic synthesizers that were being invented by others. He felt that their inventors approached the problem wrong end to, inventing a device, then searching for something to do with it, whereas he started with the music, then searched for a means of realizing it. The final version of the Free Music Machine was, however, purely electronic. In the last version, the cut paper outlines were replaced by patterns painted on rolls of clear plastic. A row of spotlights shining through the plastic projected light beams onto an array of photocells, which in turn controlled the oscillators. The inventors were working on this device at the time of Grainger's death. A full description of all permutations of Grainger and Cross' radical inventions, with illustrations, appears in Rainer Linz, "The Free Music Machines of Percy Grainger," first published in Experimental Music Instruments, Vol. 12, No.4, 1997.

Examples of the Free Music Machines are on display at the Grainger Museum in Melbourne. At 7 Cromwell only the small model remains.

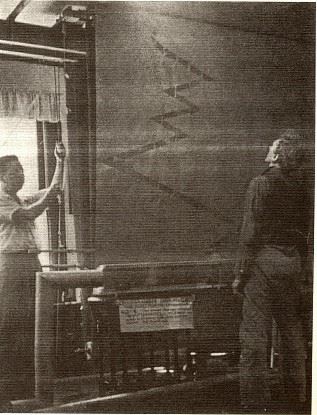

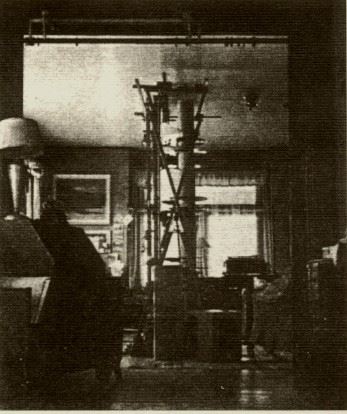

Percy's work on his experimental machines, installed in his living room, can be seen in the archival photos reproduced above: (1)Burnett Cross and Percy working on the Free Music machine, 1951, (2)Percy's "Kangaroo Pouch" Free Music machine, set up in his living room, ca. 1950. (Illustrations from Inez Bull, 7 Cromwell Place: A Loving Tribute to Percy Grainger.)

HEAR GRAINGER'S FREE MUSIC IN CONCERT ON FEBRUARY 13, 2019!

Do you want to hear what Free Music sounds like? In February, 2019, you will get a chance!

Various musicians have played the music that Grainger composed for his Free Music Machines, on a variety of instruments, including a version played on the theremin. In 2011, as part of their Downtown Music at Grace Church in White Plains, Vincent Lionti, violist with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and International Percy Grainger Society Board member, led a group from the Met Orchestra in a program that included Grainger's Free Music No.1.

And now we will get to hear them again!

At noon (12:10 PM) on February 13, 2019, at Grace Church in White Plains, you will once again get an opportunity to hear Grainger's Free Music No. 1. played by Vincent Lionti and musicians from the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra.

- Date: Wednesday, February 13, 2019

- Time: 12:10

- Location: Grace Church, 33 Church Street, White Plains, NY

- Admission: Free, but donation is gladly accepted

- Contact: www.DTMusic.org

A teaser from a past performance:

Meanwhile, you can listen to the performance of Free Music No. 1 of February 20, 2011 at Grace Church by clicking on Free Music Performance.