Percy Grainger

George Percy Grainger (1882–1961), musician, was born on 8 July 1882 at Brighton, Melbourne, only child of John Harry Grainger, architect, and his wife Rosa (Rose) Annie, née Aldridge, of Adelaide. John Grainger (1855–1917) came originally from Durham, England, and was educated there and in London and France. He migrated to Adelaide in February 1877 to take up a post in the Engineer-in-Chief's Office; he resigned in mid-1878 to concentrate on his extensive private practice. Soon after his marriage to Rose on 1 October 1880 he set up in private practice in Melbourne, where he had made a name for himself in 1879 as winner of a competition for the design of the new Princes Bridge. Later, as chief architect in the Western Australian Department of Public Works in 1897–1905, he was responsible for sections of the Western Australian Museum and Art Gallery, the Public Library of Western Australia and the Perth Law Courts, and for the first stage of Parliament House. The fine Wardens' Court in Coolgardie was designed by him. A close friend of David Mitchell and his family, he designed Dame Nellie Melba's Coombe Cottage, built at Coldstream near Melbourne in 1912. |

|

Percy Grainger's parents, his mother particularly, had little doubt that he would be 'an artist'. The boy obliged by showing precocious talent in both graphic and musical arts, the first of which developed under his father's, the second under his mother's tutelage. He had three months formal schooling at the Misses Turner's Preparatory School for Boys in Caroline Street, South Yarra, probably in 1893 or 1894. His piano studies continued from 1892 with Louis Pabst, then, after Pabst's departure for Europe in 1894, with his pupil Adelaide Burkitt. He studied harmony for a brief period, possibly with Julius Herz. His first composition, a birthday gift for his mother, dates from 1893. In September 1890 John Grainger had returned home to England on a visit, leaving his wife and son in Melbourne. Though he was back in Australia by the end of that year, he did not rejoin his family. Thereafter they met only occasionally, in Europe and Australia. Percy first came before the public eye as a pianist at a Risvegliato concert in the Masonic Hall, Melbourne, on 9 July 1894. Various other public performances included three appearances at Walter James Turner's People's Promenade Concerts at the Exhibition Building in October 1894. The boy's 'exceptional talent' was repeatedly noted. In May 1895, following a benefit concert in the Melbourne Town Hall under the direction of George Marshall-Hall, Grainger left with his mother to further his musical studies in Germany. He never returned to Australia to live but retained a ferocious nationalism, an intense love of the landscape and a rather quixotic view of the virtues of the Australian character. |

| Grainger entered Dr Hoch's Conservatorium in Frankfurt-am-Main at the minimum age of 13. Over the next four and a half years he studied piano with James Kwast, taking counterpoint and composition classes with Iwan Knorr. Several compositions date from these years, including the earliest of his settings of Kipling. He continued his lessons in painting and drawing with Georg Widmann. A Frankfurt graphic artist and amateur musician, Karl Klimsch, had a profound influence on Grainger, who later described him as 'my only composition teacher'. A solo recital given in Frankfurt on 6 December 1900 marked the end

of Grainger's student years and the beginning of a long and arduous

concert career which took him first to London, where he lived with his

mother from May 1901 to August 1914. |

Grainger benefited greatly from the close-knit strength of the Anglo-Australian community in London in the first years, but he was soon accepted by the best society. He played several times before royalty, accumulating an impressive collection of aristocratic tie-pins and cuff-links. His 1907 solo recital enjoyed the patronage of Queen Alexandra. Various landmarks highlight the growth of his pianistic career through these London years: his tour of the English provinces with Adelina Patti in 1902; his studies in Berlin with Ferruccio Busoni in 1903; his tour of Australasia and South Africa as a member of Ada Crossley's concert party in 1903–04; further extensive tours with Crossley of the English provinces in 1907, and of Australasia in 1908-09. His career as a virtuoso was enhanced by the publicly expressed admiration of Grieg, who selected Grainger to play his concerto under his baton at the Leeds Festival in 1907. Though Grieg died before the festival, Grainger's reputation as 'the greatest living exponent' of Grieg's piano music was established. That year, also, began a close friendship and professional association with Frederick Delius. From his first Danish engagements of 1904, Grainger's European touring circuit grew annually to include regular appearances throughout Scandinavia, as well as in Holland, Germany and Switzerland. In 1913 he was gave concerts in Finland and Russia. Between times, in London, he took pupils, played at 'at homes' and went about in society in the way Rose considered essential to 'getting on'. The pace was relentless and the financial pressures considerable, especially since from about 1906 he was supporting both his parents. Grainger was a man who could not afford to fail. In later years, although his earning power was immense, this financial pressure was exacerbated by an almost self-destructive generosity. |

Although there were performances of his music from as early as 1902, the Balfour Gardiner Choral and Orchestral Concerts of 1912 and 1913 really brought Grainger before the public as a composer, and as conductor of his own music. Success was instantaneous. Schott & Co., London, began publishing his music as fast as he could prepare it. There were numerous performances throughout Britain and in Europe, and he began to add conducting to his concert activities. In October 1911 he took the professional name of 'Percy Aldridge Grainger'. The Graingers' sudden departure for the United States of America at the beginning of September 1914, traumatic in its immediate effects and later repercussions, cost them the goodwill of many of their patriotic upper-class British friends. This hostility was to some extent ameliorated when Grainger joined the U.S. Army as a bandsman in June 1917. He did not see active service, but he did appear a number of times in uniform at concerts in aid of the Red Cross and other wartime charities. He became a naturalized American citizen on 3 June 1918. |

|

On being discharged from the army on 7 January 1919, Grainger embarked on what was perhaps the most flamboyant decade of his career. Lionized as a pianist and fêted as a composer, he was acclaimed as 'a latter-day Siegfried' and a worthy successor to Paderewski. Essentially the pattern of constant touring, teaching and composing did not change. Financial security came gradually: in 1921 he bought the house at White Plains, New York, in which he lived until he died. Much of his music was now published by the firm of G. Schirmer Inc., New York. His record-breaking piano piece Country Gardens, a piece which most music-lovers associate above all else with his name, was published by Schirmer's in 1919. Grainger's father had died in Melbourne of syphilis on 13 April 1917. His mother's suicide in April 1922, from despair at rumours of incest and gathering effects of syphilis, was a crushing blow. She had been his constant companion, 'managed' his business, social and emotional affairs, guided his career with single-minded purpose. Her influence was definitive; her death left Grainger with a lifetime legacy of guilt and remorse. |

| Grainger visited Australia twice during the 1920s, privately in 1924 to see his mother's family, then in 1926 on a concert tour for J. C. Williamson's. Both tours marked new departures. On the 1924 tour he began to present, albeit privately, a new type of 'lecture recital', concerts in which he talked as much as he played and in which his choice of music was determined primarily by his own cultural interests, however much these might go against the mainstream of audience taste. The results were often controversial. The 1926 tour was significant more for personal reasons. Returning home from Australia to the United States he met on board ship a Swedish-born poet and painter, Ella Viola Ström. They were married on 9 August 1928 at a public ceremony at the conclusion of a concert in the Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles. Ella was Grainger's 'Nordic Princess', a woman of outstanding beauty, 'generosity, joy-in-life and commonsense'. The marriage restored to Grainger the kind of exclusive companionship he had had with Rose. There were no children. |

Grainger returned to Australia in 1934-35, touring for the Australian Broadcasting Commission. Income from this tour established the 'Music Museum and Grainger Museum' in the grounds of the University of Melbourne. He also gave a series of twelve radio talks called 'A commonsense view of all music'. Museum and broadcasts sprang from a single impulse: the desire to educate the Australian musical public to a 'universalist' view of music, celebrating the superior achievements of the composers of the 'Nordic group', but also embracing a selection of the world's musics, folk and art, Western and non-Western, 'primitive' and 'sophisticated', ancient and modern. In these activities Grainger was projecting the universalism of his outlook. His musical eclecticism and aesthetic curiosity opened his mind to the beauties of an extraordinarily wide range of music which he variously collected, transcribed, edited, arranged, taught, performed and wrote about. The impulse to explore other cultures led him to the study of languages. He was fluent in some half-dozen European languages and their dialects, and read and studied as many more. His idiosyncratic and vigorous English prose style, exemplified in his enormous correspondence, shows the same fresh approach to language. An obverse of this eclecticism was a rather cranky concentration on notions of Nordic racial superiority and language purification. The letters also document Grainger's complex sexuality, his regular practice of flagellation, and his private absorption with what he called his 'cruelty instincts'—which were tempered in reality by an intense and tender approach to human relationships. |

In the latter part of his life, Grainger's surplus energy and time were directed into two large-scale projects: the completion and arrangement of his museum in Melbourne, and his White Plains-based experiments in what he called 'free music'. In pursuit of the imagined sound of his free music, a music unconstrained by fixed pitch, regular metre and human performance, he built mechanical music machines which combine the makeshift and the futuristic. The museum building was finished and opened on a return trip to Melbourne in 1938. His concert activity continued on a reduced scale through the 1940s and 1950s. He even began to enjoy the special advantages that came with age. 'When I take part in a concert', he wrote in 1951, 'the concert-givers are only glad that one doesn't have a stroke on stage, and they don't expect one to play the right notes any more'. The last decade of Grainger's life was shadowed by illness, and he underwent major surgery several times. Overwhelmed by a sense of his failure as a serious composer, his habit of bitter introversion intensified. Despite these inhibitions he continued his work, visiting Australia and his museum for the last time in 1955–56 and giving his last public concert performance on 29 April 1960. He died of cancer in the White Plains hospital on 20 February 1961. His gross estate was valued in the United States at $208,293. His remains were brought to Australia for burial in the Aldridge family grave in Adelaide, where his mother was also buried. His wife died at White Plains on 17 July 1979. |  The Kangaroo Pouch Free Music machine in the lounge at 7 Cromwell Place ca. 1952 |

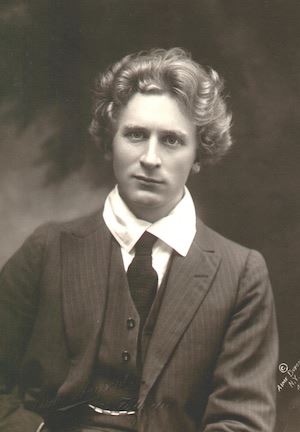

Of Grainger the pianist the New York Times's music critic Harold Schonberg wrote, 'He was one of the keyboard originals—a pianist who forged his own style and expressed it with amazing skill, personality and vigor'. This opinion may be measured against the many gramophone records Grainger made in a long recording career from 1908 to 1957. He also cut Duo-Art piano rolls with the Aeolian Co. in the United States, though these are generally regarded as less reliable guides to an artist's playing because of the possibilities of editorial interference. Something of his style at the keyboard and on the conductor's rostrum can be seen in a short silent film, probably made by Schirmer's for promotional purposes in 1920. His reputation as a composer was indelibly stamped by the success of Country Gardens, and he became known primarily as the composer of cheerfully extroverted piano pieces. In fact, he wrote very little originally for the piano. In recent years, as the growing number of recorded performances draws attention to the quantity and variety of his output, his reputation has revived and grown again. His compositions for military band are regarded as classics of the genre; his settings of British and Danish folksongs are acclaimed for their sensitivity and appropriateness. The fact that Grainger's appearance matched his talent was a not insignificant component of his success. As a young man, his Byronic good looks and his golden hair were almost as much admired and as often remarked as was the strength and vigour of his playing. In later years he affected a markedly eccentric presentation, a personal style which, if nothing else, made for good 'copy'. Grainger's pianistic feats were complemented by a vigorous athleticism; long-distance walking was a favourite if intermittent pastime. Throughout his life he abstained from alcohol and tobacco and in his middle years he became a vegetarian. There are several portraits, most notably two by Rupert Bunny (1902 and 1904) and one by Jacques-Emile Blanche (1906) in the Grainger Museum, and a charcoal sketch by John Singer Sargent (1908) in the National Gallery of Victoria. |

Kay Dreyfus, 'Grainger, George Percy (1882–1961)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/grainger-george-percy-6448/text11037, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed online 25 January 2021. This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 9, (MUP), 1983 |

Percy Grainger around 1912

Percy Grainger around 1912 Grainger in a promotional photo for Steinway in the early 1920s

Grainger in a promotional photo for Steinway in the early 1920s Bandsman Percy Grainger playing the alto saxophone, ca. 1917

Bandsman Percy Grainger playing the alto saxophone, ca. 1917 Ella Grainger in her wedding dress in 1928

Ella Grainger in her wedding dress in 1928