By Marissa Kyser, May 2019

I. OVERVIEW

As a man who obsessed over the meticulous documentation of his life, it is strange that little is known about Percy Grainger during the time he spent living in Springfield, Missouri. Though it is acknowledged that the world-famous composer moved to this area around the time of World War II, there is a lack of compiled evidence that detail his whereabouts and residence. Many researchers have contributed to understanding Grainger’s life in New York, Europe, and Australia, but most fail to describe this brief period of his life in Springfield, let alone recognize that he lived there at all. The purpose of this study is to fill this gap in the timeline of Percy Grainger’s life.

Percy and Ella Grainger moved to Springfield, Missouri in November 1940 and returned to their home in White Plains, New York in October 1943. Percy sought after the safety of his wife and career with the relocation to Springfield out of precaution, rather than cowardice. To display his support during the war, he took part in countless events that would benefit the war effort, such as fundraisers for the Red Cross, War Bond Rallies, and other charity concerts.

Though Percy frequently spent his time traveling for his performances, the time spent at the Wilshire Apartments can be viewed as entirely positive. As a man entering his sixtieth year of life, Grainger was very keen on taking advantage of the quiet lifestyle that Springfield provided him in comparison to his residence in White Plains.

"House at Springfield", photo by Percy Grainger, 1943

II. THE WILSHIRE APARTMENTS

Percy and Ella arrived by train in Springfield in June 1940 and promptly checked into the famous Colonial Hotel, located on Jefferson Avenue.[1] This short trip was planned for them to find for a permanent residence, their preference being an apartment that was “high up” and not on the ground floor. Just a few blocks south from their hotel, they discovered the Wilshire Apartments.[2]

The Wilshire Apartments, located at 520 South Jefferson Avenue, were built in 1919 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008. The terracotta-red brick building is three stories and contains six units available for rent. When submitted to the register through the National Park Service in 2008, significant detail was provided regarding the physical appearance and historical importance of the building:

The Wilshire embodies the characterizing features of this property type: a flat parapeted roof, rectangular form, symmetrical fenestration, central main entrance, and Classical Revival styling. The use of contrasting stone and terra cotta detailing, pilasters, arches, keystones, dentils, and ornamental brackets help to establish the Wilshire as a notable example of the Downtown Apartment Building property type.[3]

The building has undergone renovations since 1919; photos from the 2008 NPS application show the condition of the building prior to its most recent renovation completed in 2009. The photos from 2008 display the unit layout as it would have been in 1940. Recent photos taken ten years later (2018) depict the apartment’s layout post-renovation after being restored to reflect the “level of styling that would have been attractive to upper-middle class renters.” It was just a short walk to the public square and many local performance venues, such as the Landers Theatre, Gillioz Theater, Jewell Theater, and Electric Theater.

The Wilshire Apartments were owned by Mrs. Carrie Dell Shelpman and managed by her son, Mr. Edward J. Shelpman at this time. Edward Shelpman’s wife, Mattie, spoke with the Graingers when they initially inquired about available space in June 1940.[4]

An interview with Mattie Shelpman (recorded by Mary Jacqueline Blanton in 1977) revealed that she was hesitant to rent a room to Percy, whom she described as “odd and poorly dressed,” and presented himself wearing “work clothes, heavy work shoes, knapsack and bushy, long, reddish hair…accompanied by his plainly dressed wife.”[5] Mattie was skeptical the world-famous Percy Grainger was interested in living in Springfield, Missouri and would present himself in such strange attire. To politely mask her uncertainty, she asked the Graingers to return later that afternoon when her husband would be home to assist her. Percy and Ella agreed to the appointment and left. Meanwhile, Mattie contacted the Colonial Hotel, where the Graingers were staying for the short trip, to confirm Percy’s identity with the front desk.

Mr. and Mrs. Shelpman, reassured that they were not being deceived, met the Graingers for their afternoon appointment. Mattie recalled taking the couple up to the third floor to view Unit 6 where “they ran from room to room like excited children,” exclaiming, “We take it!”[6]

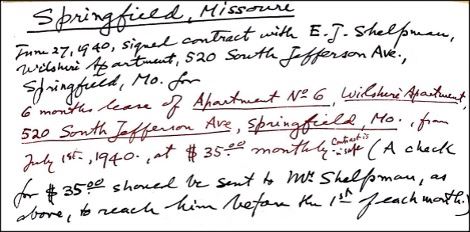

Grainger penned a handwritten note to personally record the rental agreement (See Figure 1.1):

Springfield, Missouri

June 27, 1940, signed contract with E.J. Shelpman, Wilshire Apartment, 520 South Jefferson Ave., Springfield, Mo. for 6 month lease of Apartment No 6, Wilshire Apartment, 520 South Jefferson Ave. Springfield, Mo. from July 1st, 1940., at $35.00 monthly. Contract is in safe (A check for $35.00 should be sent to Mr. Shelpman, as above, to reach him before the 1st of each month).

Figure 1.1

Percy Grainger Personal Note, Wilshire Apartments, June 27, 1940.

Grainger Museum Archives, Melbourne, Australia.

Though Grainger mentions a written contract, Mattie Shelpman stated that there was no record of a signed physical document from this agreement. The Graingers paid $35.00 a month in the 1940s to rent this two-bedroom, two-bathroom, 1400 square foot apartment. For reference, the current price in 2019 to rent Apartment 6 unit is $1,345.00 a month.[7] They would not move to Springfield and into the apartment until several months later in November.

The Wilshire Apartments

520 South Jefferson Street

Springfield, MO

Photo Taken: Marissa Kyser, 2019

III. THE GRAINGERS IN SPRINGFIELD

Whilst in Springfield, Percy composed and edited multiple works of significance including his Youthful Suite, The Power of Rome and the Christian Heart, settings from his Kipling Jungle Book cycle, The Immovable Do, and several others. He maintained his professional and personal connections via letter correspondence and continued to develop the Grainger Museum in Melbourne, Australia. His standard for performance and composition did not suffer during this time, but rather flourished.

The Springfield years yielded four formal concerts featuring Percy Grainger on June 1, 1941, January 13, September 13, and November 12, 1942. These concerts were of high interest to the public and had consistently high attendance. Performance venues included Southwest Missouri State Teachers College (now Missouri State University), Senior High School (now Central High School), and the Shrine Mosque Theater. He performed several times with the Springfield Civic Symphony under the direction of James Robertson.

In terms of leisure and entertainment, Percy was a frequent patron of the Springfield movie theaters. During weeks when he wasn’t away for a concert tour, he records attending multiple film showings in the same week. He would often partake in eateries located within walking distance of the apartment such as Davidson’s Cafeteria and Donovan’s Café.

Based on multiple instances observed in their correspondence records, it can be interpreted that Percy and Ella lived happily in Springfield and only moved back to White Plains for practical reasons. As a growing city located in the Midwest, Springfield maintained average temperatures and featured beautiful Ozarks scenery, which was plausibly attractive to an older couple. Percy makes references to Springfield in letters to Ella: “How I love Springfield & our Missouri home! It smells sweet of my angel. It is a rare love-&-art nest.” [8]

In another letter, he writes:

What a lovely state this is! So full of half-wild, half-filled, well-bread, well-watered ample … land, & full of happy comfy farms & brawny farmers. It looked its best today. Yet I slept nearly all day. I must have been all worn out![9]

IV. AFTER SPRINGFIELD

However, as all good things must come to an end, the Graingers decided to return to their home in White Plains near the end of 1943. On September 28, 1943, Percy sent a letter written in Swedish to Ella’s mother. A translated version of this letter, explaining their seemingly sudden departure, reads as follows:

28 Sept, 1943

Dear Mamma,

Ella and I have now lived in the state of Missouri (right in the middle of the United States) for 3 years. I thought that this would be safer for Ella, during the war, to live here in Springfield, Missouri, and that is why we moved here. But now we think an air attack on the American Coast is quite unlikely and that is why we, in a couple of days, move back to White Plains, where our address always is: Percy Grainger, 7 Cromwell Place, White Plains, NY.

It really is unfortunate that we must move from here, as we have been so happy here. But for practical reasons it seems better for us to live in White Plains.

It is pleasant to look back over the last 3 years and on all the artistic work we have both produced during this time period. Ella has completed a bunch of beautiful portraits—one of herself, a wonderful picture, and also about 6 others of different others of different people. Ella has also (while we lived here in Springfield) finalized her second book of Poems (“A Wayward Girl”)–which has been printed here in Springfield itself—and this book as “won” itself quite a few friends.

The war is quite far from being over. But it seems like we can assume the end is closing in, and that makes us both so happy.

Soon comes the day when Ella and I will once again travel to Sweden and visit Mamma.

That happy event we long for.

We are always talking about Mamma and hope that Mamma is well and has it as well as can be under the circumstances. Both Ella and I have been wonderfully healthy this summer.

With the dearest of greetings.

Mamma’s respectfully,

Percy[10]

After Percy Grainger returned home to White Plains, he lived there until his battle with prostate cancer caused his death on February 20, 1961. He was buried in Adelaide in March 2, 1961. It was his wish that his skeleton be preserved in the Grainger Museum for display, but this wish was not granted. At the age of 83, Ella Grainger was remarried to a gentleman named Stewart Manville in 1972. She lived in their home at 7 Cromwell Place until her death on July 17, 1979.

|

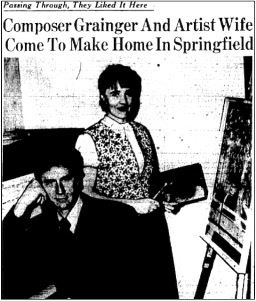

Photo from Newspaper Article

Docia Karell, “Composer Grainger And Artist Wife Come to Make Home in Springfield,” Springfield News and Leader, (Springfield, Missouri), November 10, 1940, 16.

|

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To read the complete contents of this research paper, please contact Marissa Kyser via email at mkbleu15@yahoo.com. Resources and documents used with permission from the Percy Grainger Museum, Melbourne, Australia.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES FOR THIS DOCUMENT

Blanton, Mary Jacqueline. Interviewed by Marissa Kyser. Personal Interview. Columbia, Missouri. May 1, 2019.

Blanton, Mary Jaqueline. Percy Grainger in Missouri. Thesis. University of Missouri-Columbia. 1978.

Emrie, Gail, and Debbie Shields. Wilshire Apartments. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service: National Register of Historic Places. 2007.

[1] Located at 205 South Jefferson Avenue, the Colonial Hotel was considered to be the grandest hotel in Southwest Missouri at the time. Built in 1907, this hotel had many notable occupants, including Elvis Presley, John F. Kennedy, and of course, Percy Grainger. The official ceremony naming Route 66 was also held at this famous hotel. The building was donated to Missouri State University in 1986 and sat vacant for several years until it was razed in 1997 due to extensive dilapidation that was too expensive to revert. Today, this plot of land is covered with a small university parking lot.

[2] Mary Jaqueline Blanton, Percy Grainger in Missouri, (University of Missouri-Columbia, 1978), 47.

[3] Emrie and Shields. Wilshire Apartments.

[4] Carrie Dell Shelpman (1806-1958) and Edward J. Shelpman (1868-1936) had two children. Their son, Edward J. Shelpman (1898-1999), married Mattie Lee (1902-1987) and their daughter, Isabel Shelpman (1899-1987) married Josiah Elijah Keet (1893-1973) in 1922. The family owned the Wilshire Apartments until 1970.

[5] Blanton, Missouri, 47.

[6] Ibid.

[7] The Wilshire Apartments, Web Page, Wilshire Apartments, accessed May 1, 2018.

[8] Percy Grainger, “Percy Grainger to Ella Grainger, Sept 13, 1941,” Letter, Percy Grainger to Ella Grainger Correspondence, 2016/10, Box 7, Accessed February 14, 2019.

[9] Percy Grainger, “Percy Grainger to Ella Grainger, July 3, 1941,” Letter, Percy Grainger to Ella Grainger Correspondence, 2016/10, Box 7, Accessed February 14, 2019.

[10] Percy Grainger, “Percy Grainger to Ella Grainger’s Mother, September 28, 1943,” Grainger File, Grainger Home, White Plains, New York, Accessed May 11, 2019.