by Barry Peter Ould. In the impressive roll-call of music arrangers throughout twentieth-century music, no musician looms as large in this field as the composer/pianist, Percy Aldridge Grainger. His numerous arrangements of works by other composers, as well as arrangements of his original and folk-music settings, present a body of work which is perhaps unique in the annals of music history. Grainger’s musical interests covered a wide spectrum from medieval polyphony to the twentieth-century, which culminated in his own early experiments in producing electronic music on ‘free music’ machines.

Grainger’s development as an arranger can be roughly divided into three periods. His earliest work as an arranger of traditional music can be dated to 1898. when he took the song ‘Willow Willow’ from William Chappell’s ‘Old English Music’ and wrote a new accompaniment to the existing melody. This was soon followed by 25 traditional melodies from Augener’s ‘Minstrelsy of England’ all with new accompaniments by the 16-year-old Grainger. In 1900, during a visit to West Argyllshire in Scotland, the young Grainger was heavily influenced by what he saw and heard and this was to have a profound effect on the music he produced thereafter.

His next set of arrangements was 12 songs from the Scottish collection ‘Songs of the North’, for which he wrote new piano accompaniments. Another two pieces from the same collection were arranged for a cappella voices, and it is in these settings that the beginnings of Grainger’s unique harmonic style can be heard. Grainger continued to make new settings of existing source material more or less up until he embarked on collecting traditional folk songs. The years leading up to this important phase of his life were filled with an insatiable appetite for work.

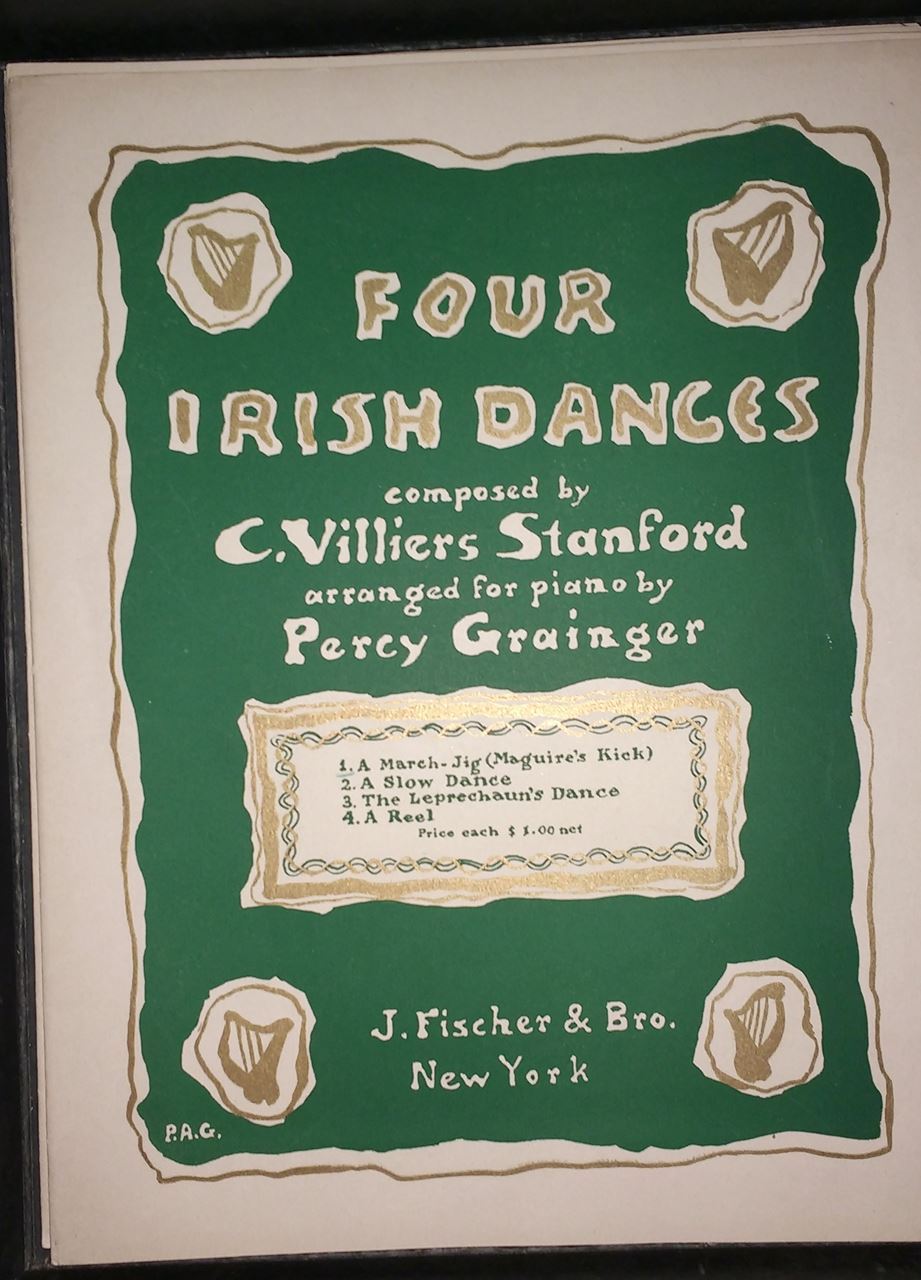

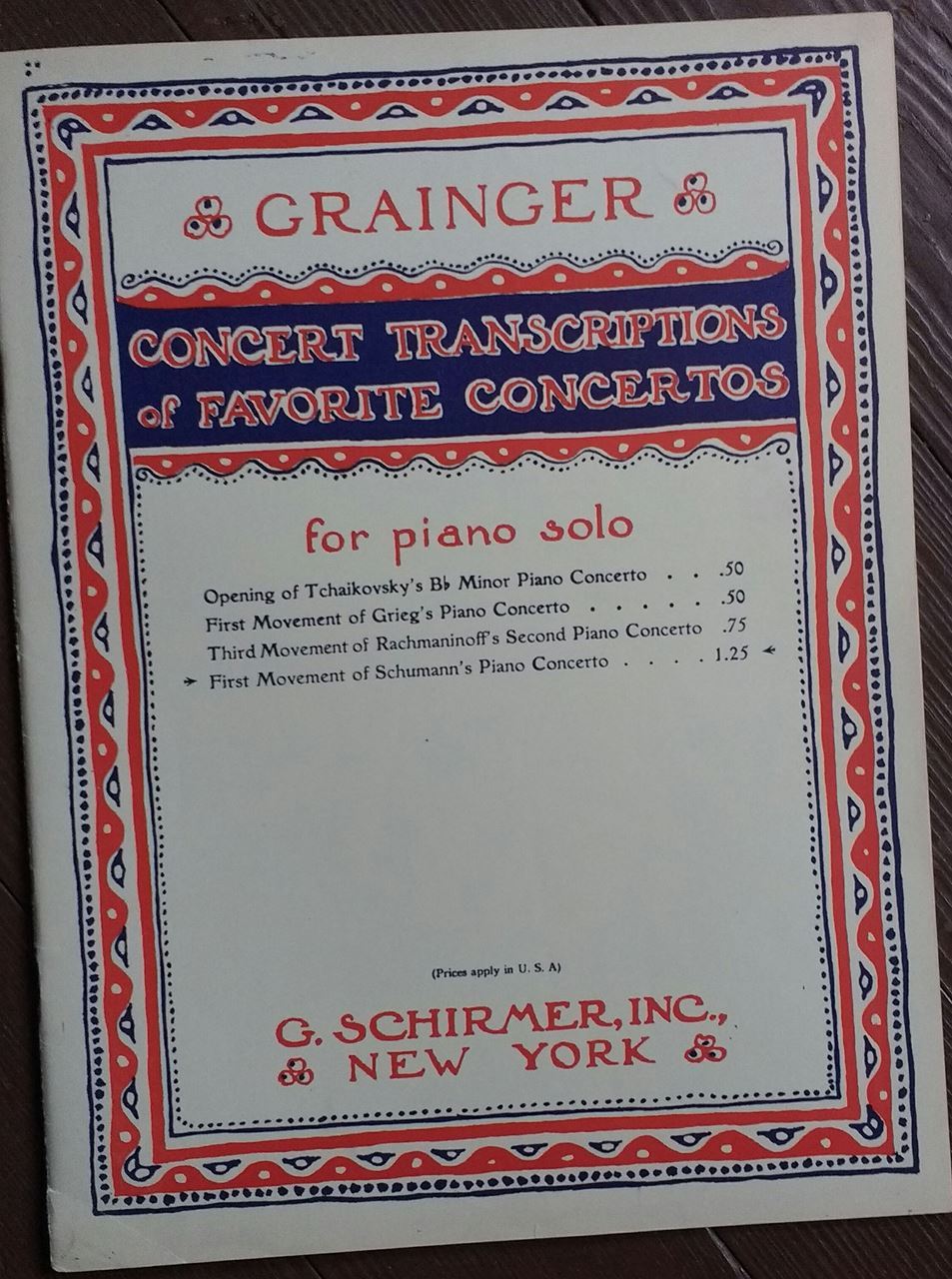

His first public recital as a pianist took place in 1901, but he was also very busy playing at private functions. It was during these ‘At Homes’ recitals that Grainger came into contact with many of the leading musicians and composers of the day. These early years in London saw the composition of his paraphrase transcription of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Flower Waltz’, his first venture into that particular art form and piano transcriptions of 4 Irish Dances by his friend and mentor, Charles Villiers Stanford. This would in turn lead to a series of piano transcriptions on pieces he particularly adored and thus securing him a position amongst the ranks of composer-pianists who were all attracted to this genre.

His first public recital as a pianist took place in 1901, but he was also very busy playing at private functions. It was during these ‘At Homes’ recitals that Grainger came into contact with many of the leading musicians and composers of the day. These early years in London saw the composition of his paraphrase transcription of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Flower Waltz’, his first venture into that particular art form and piano transcriptions of 4 Irish Dances by his friend and mentor, Charles Villiers Stanford. This would in turn lead to a series of piano transcriptions on pieces he particularly adored and thus securing him a position amongst the ranks of composer-pianists who were all attracted to this genre.

It was also during this period that Grainger met for the first time, his musical hero, Edvard Grieg. He had long been a fervent admirer of the Norwegian’s music. While still a boy in Australia, he had come under the spell of Grieg’s piano music, taught to him by his mother, Rose. His earliest orchestral arrangements were of three of Grieg’s ‘Lyric Pieces’ from op. 12. scored in July 1898, which predated his first song arrangement of ‘Willow, Willow’ by some 4 months. In 1902, during his stay at Waddesdon Manor, near Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire, Grainger penned perhaps his most famous arrangement. It was his choral setting of the ‘Irish Tune from County Derry’ which has in latter years been wrongly attributed the title of ‘Danny Boy’. This sumptuous melody was to be arranged in many different ways during Grainger’s lifetime, but the first published edition of his ‘elastic’ scoring concept was a highly chromatic version of the tune.

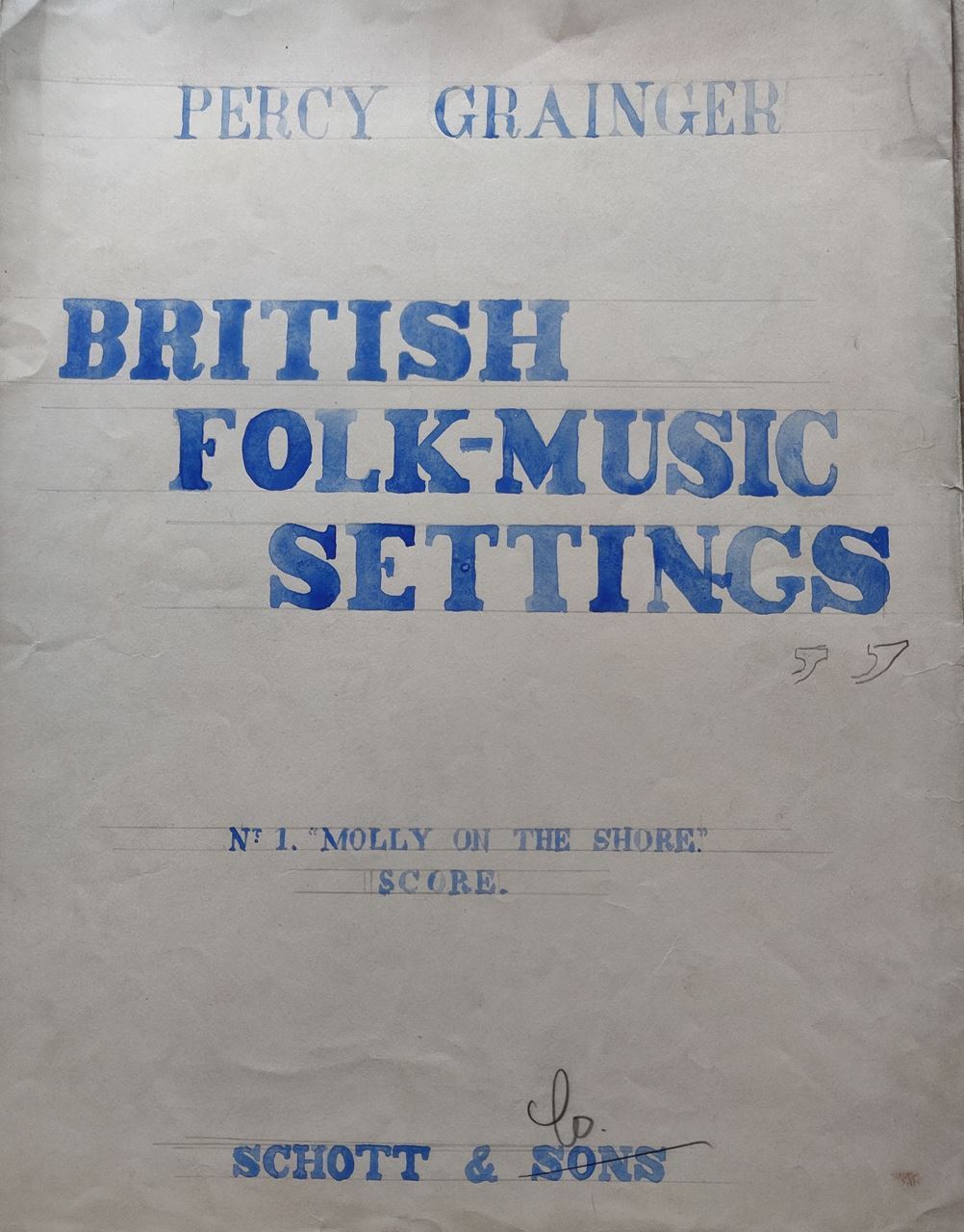

In 1904, a meeting with Lucy Broadwood inspired Grainger to start collecting folk songs in the field. The material he collected between 1905 and 1909 would become his new source of inspiration, leading to the creation of one of his major musical achievements: the composition of the series ‘British Folk Music Settings’, which forms the largest collection of pieces among the generic headings he gave to his compositions. The folk songs he collected were mainly from Lincolnshire and Gloucestershire, but he also notated a number of sea chanties from John Perring and Charles Rosher, a deep sea fisherman and retired sailor respectively. It was from Rosher that he collected ‘What shall we do with the drunken sailor’ used to great effect in his ‘Scotch Strathspey and Reel’. Perring provided ‘Shallow Brown’, perhaps one of Grainger’s greatest settings. Grainger also visited Denmark where he undertook several expeditions to collect material, the last being in 1922. Again, the songs he collected in Denmark would be used in a series of compositions entitled ‘Danish Folk-Music Settings’ of which his ‘Danish Folk-Music Suite’ for orchestra is the crowning achievement.

In 1904, a meeting with Lucy Broadwood inspired Grainger to start collecting folk songs in the field. The material he collected between 1905 and 1909 would become his new source of inspiration, leading to the creation of one of his major musical achievements: the composition of the series ‘British Folk Music Settings’, which forms the largest collection of pieces among the generic headings he gave to his compositions. The folk songs he collected were mainly from Lincolnshire and Gloucestershire, but he also notated a number of sea chanties from John Perring and Charles Rosher, a deep sea fisherman and retired sailor respectively. It was from Rosher that he collected ‘What shall we do with the drunken sailor’ used to great effect in his ‘Scotch Strathspey and Reel’. Perring provided ‘Shallow Brown’, perhaps one of Grainger’s greatest settings. Grainger also visited Denmark where he undertook several expeditions to collect material, the last being in 1922. Again, the songs he collected in Denmark would be used in a series of compositions entitled ‘Danish Folk-Music Settings’ of which his ‘Danish Folk-Music Suite’ for orchestra is the crowning achievement.

A series of eight concerts between 1912-1913, organised and sponsored by Henry Balfour Gardiner, a fellow student at Hoch’s Conservatory in Frankfurt, presented Grainger with an opportunity to present some of his choral and orchestral arrangements for the first time. At the first of these concerts, a setting of a Faeroese dance folk song ‘Father and Daughter’, with guitar ensemble was a huge success. It brought Cecil Forsyth’s attention to Grainger’s unique scoring for guitars which he later used in his book on orchestration. The fifth concert included one of Grainger’s earliest orchestral settings from folk music sources, namely ‘Passacaglia on Green Bushes’.

A publishing deal with Schott and Co. was secured in 1911 and, after the success of a handful of popular pieces including ‘Shepherd’s Hey’, Grainger was encouraged to make piano arrangements of them to widen their popularity. Thus the process of transcribing his own pieces began. Whilst Grainger’s original piano works are almost without exception transcriptions (the majority of his piano versions were made after their original instrumental or orchestral scores were composed), it is in the thirty or so transcriptions of other composers’ music that his originality as a composer for the piano shines forth.

After this period Grainger and his mother departed for the United States. This third phase was to be the most extended. As his ideas for new works were drying up, especially so after his mother’s death in 1922, Grainger undertook the constant rearranging of previous compositions. A brief period in the United States Army as bandsman gave him the opportunity of writing for the military band. It was during this time that he arranged a number of his popular pieces for band. During his London years he had acquired a thorough knowledge of wind instruments, augmented by his time as bandsman, and this would prove invaluable when he came to write such masterpieces as ‘A Lincolnshire Posy’. However, the anonymity of army life however did not last long and it was soon discovered that his true talents lay as a concert pianist. In 1918, he was coaxed into giving a piano recital in aid of War Bonds. For this recital he dished up the piece to which his name would be inextricably linked with for the remainder of his life. The tune had been given to him ten years earlier by Cecil Sharp who had collected it from traditional sources and his arrangement of ‘Country Gardens’ would provide Grainger with an income for life.

After this period Grainger and his mother departed for the United States. This third phase was to be the most extended. As his ideas for new works were drying up, especially so after his mother’s death in 1922, Grainger undertook the constant rearranging of previous compositions. A brief period in the United States Army as bandsman gave him the opportunity of writing for the military band. It was during this time that he arranged a number of his popular pieces for band. During his London years he had acquired a thorough knowledge of wind instruments, augmented by his time as bandsman, and this would prove invaluable when he came to write such masterpieces as ‘A Lincolnshire Posy’. However, the anonymity of army life however did not last long and it was soon discovered that his true talents lay as a concert pianist. In 1918, he was coaxed into giving a piano recital in aid of War Bonds. For this recital he dished up the piece to which his name would be inextricably linked with for the remainder of his life. The tune had been given to him ten years earlier by Cecil Sharp who had collected it from traditional sources and his arrangement of ‘Country Gardens’ would provide Grainger with an income for life.

After his time in the United States Army he resumed work as a concert pianist and his vigorous nature never allow him to rest. Grainger’s remaining years in the United States were oriented towards education, and a series of teaching posts were made available to him. This provided him with the opportunity to make arrangements of pieces for multiple pianos so that his piano students would be able to play alongside him and thus accustom themselves to playing in an ensemble. For the more gifted pupils, he made special two-piano arrangements of some of his original works and folk music settings.

It was at the Chicago Music College beginning in the summer of 1919, that the two first numbers of his ‘Free Settings of Favourite Melodies’ were written out. The ‘Hornpipe’ from Handel’s ‘Water Music’, however, appears to have been thought out earlier than this. It is a straightforward treatment of the original melody, though technically more demanding than it sounds. The second, Brahms’s ‘Wiegenlied’ (‘Cradle Song’) op. 49 no. 4, is a contemplative study characterised by much arpeggiation. The third piece in the series is a transcription of the song ‘Nell’ op. 18 no. 1 by Fauré. Grainger’s filigree treatment of the melody was made in the February of the same year in which Fauré died. The transcription of one of Fauré’s most poignant love songs, ‘Après une rêve’ op. 7 no. 1 followed in 1939. In the twilight years of Grainger’s life, although frail, he would often be heard playing these two Fauré melodies. Before 1920, work commenced on ‘Ramble on Love’ with the full title Ramble on the Love-duet in the Opera ‘The Rose-Bearer’ [Der Rosenkavalier] FSFM No. 4. But it was his mother’s suicide in 1922 that drove Grainger to complete this most elaborate of all his piano paraphrases, with her name obliquely enshrined in the title.

For the Chicago Music College’ summer school in 1928, Grainger made the first of his impressive transcriptions for percussion ensemble of Debussy’s ‘Pagodes’ (Estampes) whom Grainger had first met during his years in London. In 1932, Grainger was appointed associate professor and chairman of the music department at New York University and, through the auspices of Gustave Reese, Grainger was introduced to a recording of medieval music by the English musicologist, Dom Anselm Hughes. This experience was to bring Grainger’s attention to a body of music which would preoccupy him for the remainder of his life. His work on arranging and trying to popularise this music lead to the publication of a series of pieces entitled ‘English Gothic Music’.

In the following years whilst visiting his homeland, Grainger made a series of transcriptions from recordings of ethnic music from the Pacific regions and the harmonisation of a Chinese tune, ‘Beautiful Fresh Flower’, which he had read about in A Theory of Evolving Tonality by the American musicologist, composer, organist and conductor Joseph Yasser. The melody of ‘Beautiful Fresh Flower’ was also used by Puccini in his opera Turandot.

From 1930 onwards Grainger began lecturing and teaching at the National Music Camp at Interlochen, Michigan, and for these annual events he turned his attention to making many arrangements of works by different composers, among whom J. S. Bach took a central role. At the same time, he began a series of masterly arrangements under the heading ‘Chosen Gems for Winds’ including works by Josquin, de Cabezon, William Lawes and Eugene Goosens as well as pieces made available to him from his collaboration with Dom Anselm Hughes. A similar set of arrangements for strings was also undertaken, and many of these works were performed during the concerts Grainger organised at the Interlochen summer music schools. For his final concert in the summer of 1944, he made a transcription of Ravel’s ‘La Vallée des Cloches’ for tuneful percussion and strings. This was his second transcription of a Ravel piano work. In 1934, he had transcribed ‘Le Gibet’ for piano and marimbas, but the score has never come to light and is presumed lost.

From 1930 onwards Grainger began lecturing and teaching at the National Music Camp at Interlochen, Michigan, and for these annual events he turned his attention to making many arrangements of works by different composers, among whom J. S. Bach took a central role. At the same time, he began a series of masterly arrangements under the heading ‘Chosen Gems for Winds’ including works by Josquin, de Cabezon, William Lawes and Eugene Goosens as well as pieces made available to him from his collaboration with Dom Anselm Hughes. A similar set of arrangements for strings was also undertaken, and many of these works were performed during the concerts Grainger organised at the Interlochen summer music schools. For his final concert in the summer of 1944, he made a transcription of Ravel’s ‘La Vallée des Cloches’ for tuneful percussion and strings. This was his second transcription of a Ravel piano work. In 1934, he had transcribed ‘Le Gibet’ for piano and marimbas, but the score has never come to light and is presumed lost.

Such is Grainger’s breadth and vision that if for some strange reason all music apart from Grainger’s arrangements were to disappear, we would be left with a body of work which would give us a fundamental understanding of the development of music from different cultures throughout the ages. It is unfortunate that Grainger’s reputation as a composer is largely based on a handful of popular piano arrangements, while the bulk of his inventive and highly individual settings of folk-music, together with his arrangements of a wider gamut of music from all periods, and his own original compositions, for the most part go unperformed and unheard. The multifaceted genius of Grainger the music arranger has yet to be fully appreciated.